A Comprehensive Guide to Writing Captivating Short Stories for Children

In addition to providing entertainment, children’s short stories foster curiosity, bravery, and empathy. Though it requires a unique touch to create stories that genuinely connect with young readers, writing them is enjoyable and fulfilling.

The Enchantment of Children’s Short Stories: An Overview

Children can unleash their imaginations through short stories. A bunny that can talk goes on adventures. A good-hearted princess gains important life lessons. And somewhere in those few pages, kids learn that reading isn’t only something adults bug them about, but that it’s genuinely enjoyable.

You can’t write down to children, which is the problem with writing for them. Children can spot condescension at a distance. They are looking for stories that will stimulate their imagination and honor their intelligence. Every children’s writer aims for that sweet spot.

Good children’s stories, according to one person, are about writing up to children’s imaginations rather than writing them down. Whoever said it knew what they were supposed to do. Children’s imaginations are enormous. It’s your responsibility as a writer to stay up to date with them, not to simplify them.

The Essential Components of a Short Story

Structure is necessary for all stories, but especially for short stories. Stories are not made up of a series of unrelated incidents. They’re just… sporadic occurrences. Chaos has purpose when it is organized.

| Element | Description | Example |

| Plot | The sequence of events that drive the story | A boy finds a magic key and sets off to find the door it unlocks |

| Characters | The people or animals who bring life to the tale | Curious rabbit, kind witch, or brave child |

| Setting | The time and place where the story unfolds | An enchanted forest, a moonlit beach, or a cozy village |

| Conflict | The challenge or problem that needs solving | The dragon steals the village’s food supply |

| Resolution | How the problem is solved and what is learned | The villagers befriend the dragon and share their meals |

These components are not optional ornaments. Your tale is held together by these bones. The entire thing falls apart if you skip one.

Selecting the Proper Theme for Your Viewers

Not every age group can enjoy every narrative. Preschoolers won’t be interested in your intricate mystery by the second page. You can hear ten-year-olds rolling their eyes when you write repeated baby stuff for them.

| Age Group | Ideal Themes | Example Topics |

| 3–5 years | Friendship, colors, simple adventures | “The Rainbow Caterpillar” |

| 6–8 years | Teamwork, imagination, kindness | “Luna and the Lost Star” |

| 9–12 years | Bravery, problem-solving, humor | “The Time-Traveling Notebook” |

Quick Tip:

Connect the theme of your narrative to experiences that children have on a daily basis, such as sharing toys, having strange curiosity, family dynamics, school turmoil, or those crazy dreams that seem so real.

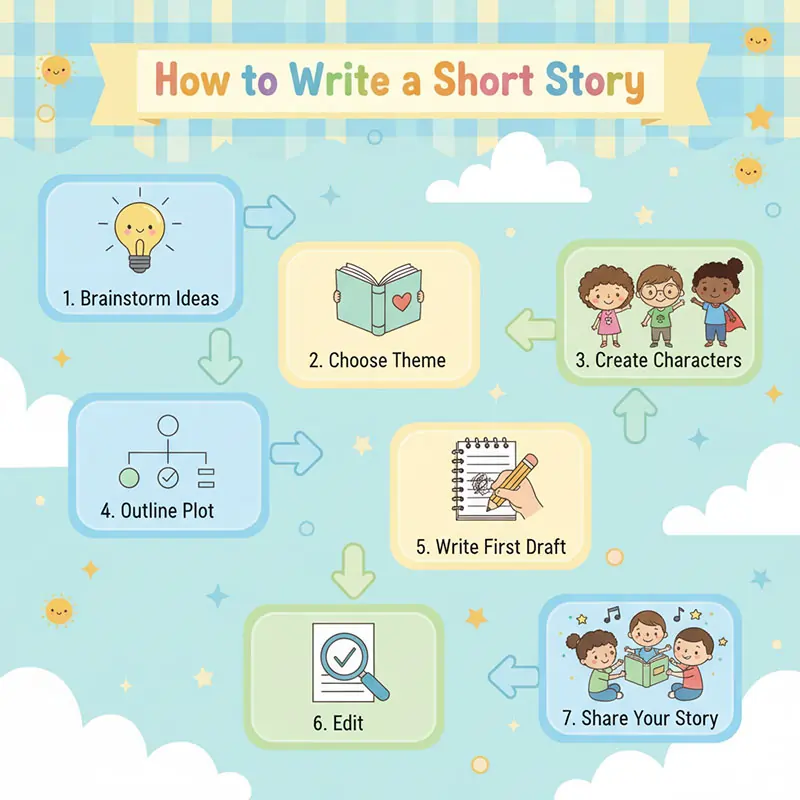

✍️ Step-by-Step Short Story Writing Guide

Let’s actually write anything now. This is the method that works when you’re looking at a blank page and wondering why you thought you could write for children.

🪄 Step 1: Have an Idea First

You may find ideas everywhere if you pay attention. One of your nephew’s strange questions. That strange dream you experienced. What if the stapler on your desk could speak?

Consider the following issues that challenge reality:

- What if animals could communicate, but only with children?

- What occurs if a cloud grows weary of raining?

- What if your shadow took a different course of action?

🎭 Step 2: Imaginative Story Concepts

“The Pencil That Forgot to Write” – “Grandpa’s Invisible Garden” – “The Butterfly Who Couldn’t Fly”

Take a strange “what if” question as a starting point and see where it takes you.

Example Character Sketch:

| Character | Personality | Goal | Flaw |

| Benny the Bunny | Curious, clumsy | Find his lost carrot | Gets distracted easily |

Tip: Give your main character a simple goal and a relatable flaw — that’s what makes them lovable!

🌍 Step 3: Set the Scene

Make the setting of the story more tangible for readers. However, keep descriptions brief and engaging—children don’t require three paragraphs about architecture.

For instance, “The sun peeked through the candy-colored clouds as tiny houses sparkled like gumdrops.”

A single sentence. whole world created. That is the level of efficiency required by children’s writing.

⚔️ Step 4: Construct the Conflict

It’s conflict that draws readers in. A character simply strolling around enjoying themselves is all that exists when there is no conflict. That’s just a nice afternoon, not a story.

Children don’t require conflict to be gloomy or frightening. It may be humorous, sentimental, or small. All you need is for your character to care about the stakes.

Here are some examples:

A bear unable to hibernate after losing his blanket; a girl running out of sugar to make cookies; and a robot that doesn’t get why people embrace.

If the character dealing with the simple situation finds meaning in it, then it works.

🪞 Step 5: Establish the Resolution and Climax

Tension reaches its pinnacle at the climax. This is the culmination of everything. Finally, Benny the Bunny finds his carrot, but hold on, a bird also wants it! collision of conflict.

Then there’s the conclusion: they become friends after sharing it. Issue resolved, lesson organically incorporated.

Children’s endings must be resolved. Not necessarily “happily ever after,” but a sense of fulfillment.

Possible Endings:

- Happy: Problem solved joyfully—everyone smiles

- Surprise: Unexpected twist that makes youngsters laugh and gasp

- Moral: The story imparts empathy, patience, or honesty without being overtly didactic.

Related reading: Moral Short Stories for Kids

✏️ Step 6: Include a Moral or Message

Take note of “optional”? Not every children’s tale requires a clear lesson. An enjoyable experience that piques the imagination is sufficient at times.

However, if a lesson is included, allow it to flow organically from the narrative. To lecture readers, don’t halt the activity.

For instance,

- Sharing makes everyone happy.

- Being different makes you special.

- Kindness always finds its way back.

These are effective because they are the conclusions drawn by characters rather than adult lecturers.

🎨 Step 7: Apply Your Imagination and Rhythm

Rhythm and repetition help stories stick in the minds of young readers and make reading aloud enjoyable.

For instance, “He jumped and hopped, he flipped and flopped, until he found his way back home.”

The sentence has a bounce because of that beat. As children read it, they sense the movement. That’s the charm of well-written children’s literature.

The visual idea is a sound-wave graphic that illustrates how rhythm adds a musical element to storytelling.

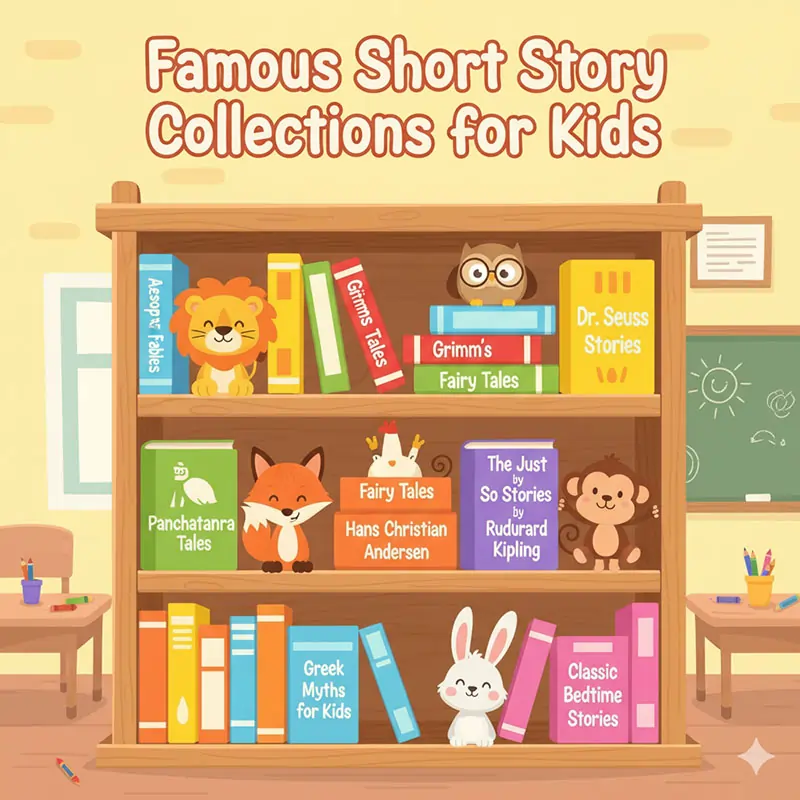

📚 Examples of Well-Known Children’s Short Stories

Great storytelling strikes a balance between imagination, enjoyment, and education without coming across as overbearing, as these classic tales demonstrate.

| Story | Author | Theme | Lesson |

| The Tortoise and the Hare | Aesop | Patience | Slow and steady wins the race |

| The Very Hungry Caterpillar | Eric Carle | Growth | Change can be beautiful |

| Where the Wild Things Are | Maurice Sendak | Imagination | Home is where love lives |

| The Giving Tree | Shel Silverstein | Kindness | Giving brings happiness |

| The Gruffalo | Julia Donaldson | Bravery | Wit can overcome fear |

Related reading: Fairytale Stories

Design a bookshelf-style infographic titled “Famous Short Story Collections for Kids.” Show colorful book spines labeled with titles such as Aesop’s Fables, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Dr. Seuss Stories, Panchatantra Tales. Add smiling cartoon animals peeking between books and a cheerful classroom background.

🪶 Advice for Increasing Story Engagement

Composition for children is more than just simplicity; it involves feeling, astonishment, and acknowledging their intelligence.

💡 Writing Inspiration:

- Make use of vivid verbs: “She ran” usually lacks the energy that “She dashed across the meadow” does.

- Incorporate humour: Children enjoy a good joke or unexpected turn of events. “The dragon sneezed and accidentally toasted his own toast” makes people giggle.

- Incorporate dialogue: Allow characters to speak in their own voices rather than as little adults. Squeaking, the mouse said, “Hey, that’s my cookie!”

- Keep phrases brief: A simple rhythm improves flow. Children who read on their own require small, manageable pieces.

It will be enjoyable to read aloud if it sounds enjoyable when spoken. You should always test your story aloud. The stories that youngsters beg to hear over and over again are separated by these tips.

Related reading: Funny Short Stories for Kids

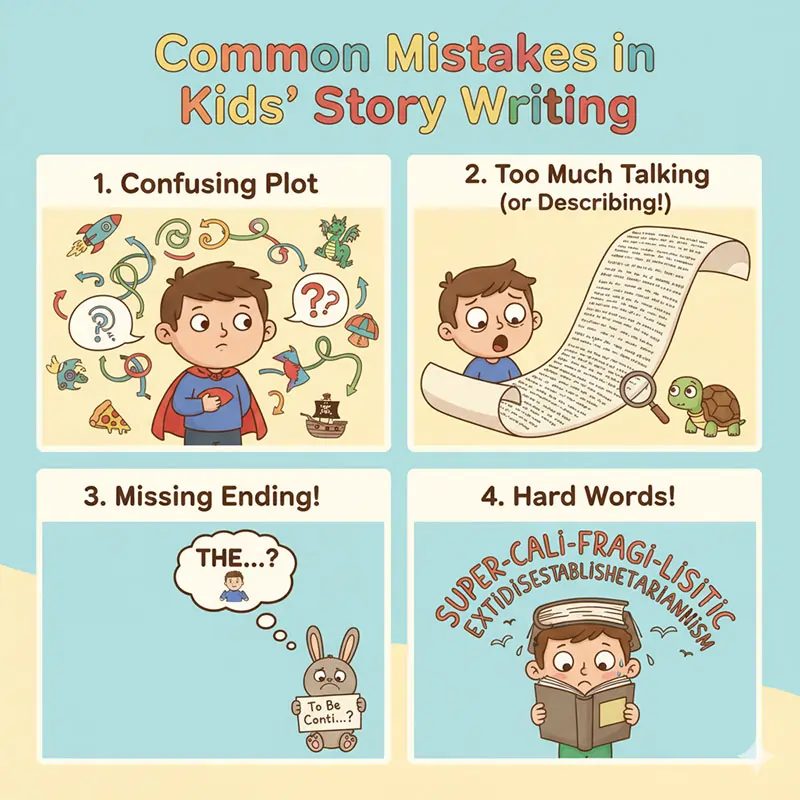

🚫 Typical Errors to Steer Clear of

Even seasoned authors make mistakes when writing for young readers.

To avoid these traps:

| Mistake | Why It’s a Problem | How to Fix It |

| Using complex vocabulary | Kids lose interest | Use age-appropriate language |

| Too much description | Slows down the pace | Focus on action and dialogue |

| Moral feels forced | Feels like a lecture | Let the lesson emerge naturally |

| Characters act too mature | Breaks believability | Keep behavior age-accurate |

| Long, dragging endings | Kids lose focus | End with a quick emotional payoff |

You may become a professional children’s writer more quickly than anything else by avoiding these blunders.

Create a cartoon-style illustration showing “Common Mistakes in Kids’ Story Writing.” Include 3–4 panels or boxes with mini scenes — e.g., a confused child mixing up plot points, a long boring paragraph, missing ending, and overcomplicated vocabulary. Use light humor and expressive characters to keep it friendly and educational.

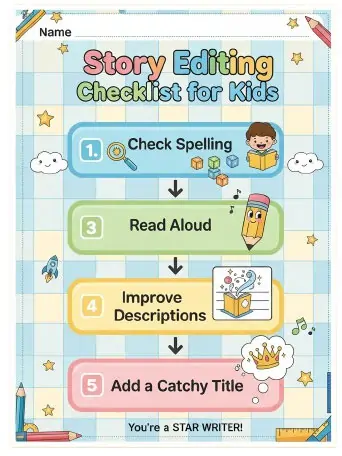

✂️ Revising and Refining Your Narrative

Is the first draft finished? Congratulations! The real job now starts. When stories are edited well, they become amazing.

🧰 Checklist for Short Story Editing

✅ Verify your grammar and spelling—it’s simple but crucial

✅ Read aloud to identify difficult phrases and make sure sentences flow naturally

✅ Eliminate words that you use too often; you definitely overuse some of your favourites

✅ Test your rhythm by reading aloud; if you stumble, you have to rewrite

✅ Ask parents or real children for input; they’ll let you know what doesn’t work.

The truth. Initially, drafts are always awful. The magic happens in the editing process. Revision should be welcomed as a necessary component of the creative process rather than a penalty for making a mistake in the first place.

Create a neat flowchart titled “Story Editing Checklist for Kids.” Include steps like: Check Spelling → Read Aloud → Fix Grammar → Improve Descriptions → Add a Catchy Title. Use colored checkboxes and icons like magnifying glasses, pencils, and books. Design should look like a printable worksheet for children.

❓ FAQs About Composing Children’s Short Stories

Q1. How long should children’s short stories be?

For early readers, 300–1000 words is ideal; for older children, 1500–2500 words. shorter than you might imagine. Each word must be worthy of being used.

Q2. Does morality always have a place in children’s stories?

No. An enjoyable experience that arouses interest or laughter is valuable even in the absence of clear teachings. When morality don’t fit naturally, don’t force them.

Q3. Is it okay to employ animals as the main characters?

Sure! Children like talking animals or toys that are anthropomorphic. It’s easier to explore genuine feelings when putting some distance from reality.

Q4: How can I make my tale unique?

Combine well-known subjects with fresh viewpoints. Do you have a story about a dragon that fears knights? That’s new. Treasure hoarding by a dragon? finished.

Q5. Do I need to draw my story?

Sure, if you can. Visuals greatly increase the interest level of children’s stories and simplify difficult concepts. Good stories, however, can also be told without pictures.

Writing Tales That Remain in Their Hearts: A Conclusion

It is a magical act to transform basic words into worlds that children want to live in when writing short stories for them. It isn’t about being perfect. It has to do with connecting.

When a child begs to hear the story again, gasps at your twist, or smiles at your joke, you’ve accomplished. Their memories are shaped by your words, which also influence their worldview.

Even after the last page is turned, youngsters will desire to live in a good children’s book. That is the objective. Not commercial success, though that’s lovely, or literary honors. The true objective is to produce content that appeals to young readers.

Find your strange “what if” question, pick up your pen, and begin writing stories that make young readers everywhere laugh, be nice, and be curious. The stories only you can tell them are what they’re waiting for.